Earlier this year, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin brought suits in their respective district courts against Delaware for wrongfully claiming millions of dollars’ worth of abandoned property. The abandoned property at issue revolves around a check-like instrument issued by the money transfer company MoneyGram.

Earlier this year, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin brought suits in their respective district courts against Delaware for wrongfully claiming millions of dollars’ worth of abandoned property. The abandoned property at issue revolves around a check-like instrument issued by the money transfer company MoneyGram.

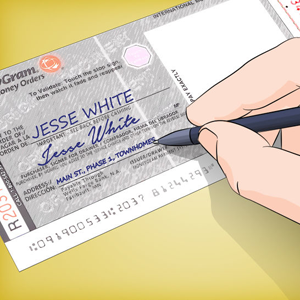

MoneyGram is the nation’s largest provider of money orders. Its headquarters is located in Texas, but it does business in all fifty states. Along with money orders, MoneyGram also issues what they call, “official checks.” These checks essentially work the same way as money orders, except that they reflect larger amounts of money and are sold at financial institutions, such as banks.

When these checks go unclaimed, they become abandoned property and MoneyGram remits the money to Delaware, where the company is incorporated. The unclaimed checks provide Delaware’s third largest source of revenue and makeup 15 percent of the state government’s annual income. The checks are expected to total more than half a billion dollars in the current fiscal year.

But now, other states want a piece of the pie.

Following Pennsylvania and Wisconsin’s lead, 21 other states filed a joint suit against Delaware in the United States Supreme Court asking for a combined $150 million. The suit is led by Texas, which stands to gain $10 million. Delaware filed its own suit in the Supreme Court against Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, after which Pennsylvania filed a motion to move its case to the Supreme Court as well.

Under Article III of the Constitution, the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction over this issue because it involves resolving a dispute between the states. Having original jurisdiction means the Court has the authority to decide a case in the first instance like a trial court.

The resolution will likely come down to the Court’s application of the Disposition of Abandoned Money Orders and Traveler’s Checks Act (12 U.S.C. § 2501 et seq.). The statute was enacted as a direct response to the Supreme Court’s decision in a 1972 case, Pennsylvania v. New York, 497 U.S. 206 (1972). In Pennsylvania v. New York, the Supreme Court held that in the absence of record evidence of the address of the owner of an un-cashed money order, the state of the holder’s corporate domicile (i.e. the state of incorporation) had the right to escheat the sums owed on the money order. In direct contrast, the Disposition Act provides that if a “money order, traveler’s check, or similar written instrument” goes unclaimed, the State in which the instrument was purchased “shall be entitled exclusively to escheat or take custody of the sum payable.”

The Supreme Court is not obligated to take the case, but if it does, it will need to decide if the Disposition Act applies to the official checks in question. If it decides that the Act does indeed apply to official checks, Delaware will not only owe over $150 million, but it will depreciate its future revenue.